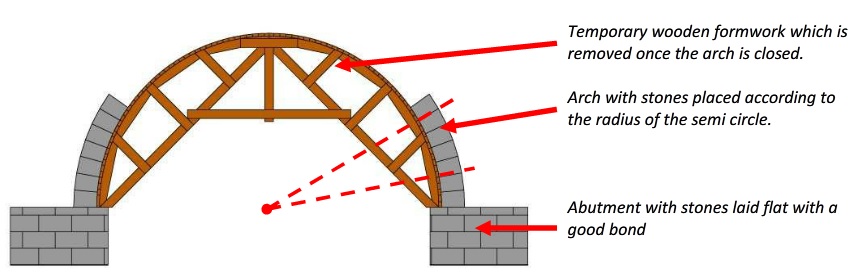

Dirt seeps between the joints over time and will hold water, causing frost heaving of the structure regardless of whether it is laid on the rock or dirt. For motarless work the arch can simply be laid on hard subsoil below the streambed, provided the chance of erosion isn’t too high. If you are blessed with bedrock that is only a couple of feet or so under the ground you can simply lay the foundations on this otherwise, for mortared work at least, the foundations must be placed below the frost line. The next thing to do is to lay the foundations. Regardless, we’d recommend making a template of the angle needed for this purpose so that the stones used will be approximately the correct shape. Laying the stones such that a sloping face is created for the arch to rest on is a valid alternative. For segmental arches, “skewbacks” of some sort will be needed these are triangular stones on which a segmental arch rests. Other arch types are simply variants and other applications of these two basic arches. There are two basic arch shapes: the Roman arch, which is simply half of a circle, and the segmental arch, which is a flatter arc than a Roman arch. At the ends can also be seen the “skewbacks” - in this case pieces of sandstone cut to 30-degree angles to accommodate the 120-degree segmental arch being built. Alternatively, rebar or even PVC pipe can be bent and held into an arch shape, saving the need for cutting wood, though the resultant shape will be more parabolic in nature unless somehow forced into the correct shape.Īn example of formwork for a stone arch bridge we built. Once this is decided, a little bit of geometry will allow one to determine the shape of the temporary formwork that will be required to build the arch.Ī wooden form can be cut out of plywood with slats nailed on top, or, if you have a lot of scrap plywood, you can attach numerous plywood pieces cut to the right shape together, each spaced a few inches apart. Once the location of the bridge is determined, the next step is to create a design, determining the number of arches and the shape they will take. Of course, with practice, it will become easier and easier to build bigger and bigger bridges. We might add that, while with a bit of determination it can certainly be done, we would strongly discourage the amateur from undertaking long spans! Long spans require more precision to stand. It is typically desirable for the underside of the top of the arch to be level with or higher than the banks however, this can cause a steep grade. Roughly determining the area of water in the ditch at a given point allows for a calculation of how much total open surface area the arch(es) must have to accommodate maximum flows. This may, however, be very inconvenient as not only will it tend to muddy up any paths and the bridge itself, but it is during heavy flows when a bridge is most useful. For small ditches it will not hurt anything for water to flow around or over the bridge. If possible, during heavy floods, determine how much water there is roughly. The first thing to do, of course, is to determine the location of the bridge and the amount of waterway it is to handle. We assume no liability for use or misuse of this information, but we do hope this will be helpful to the DIY enthusiast. We’ve based it on several small bridges we built, including some lessons learned afterwards from the process. We have provided this short guide as a very general rule of thumb the details of your construction will vary. The question is how do you go about doing it? Such a structure is scenic and, of course, lends a fine touch to landscaping. It is often desired to build a stone arch bridge.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)